Professor Steven Tingay, Curtin University, Perth

↧

TEDx Perth: Science, Art, Reconciliation

↧

Special Event: Corroboree Sydney

Four days of Indigenous cultural experience and interactions, including a talk on Aboriginal Astronomy by Professor Ray Norris.

Date: 16 November 2013 to 19 November 2013

Location: Australian Museum, Indigenous Australians: Australia’s First Peoples gallery

See more at: http://australianmuseum.net.au/event/corroboree#sthash.D4XHdgoB.dpuf

Date: 16 November 2013 to 19 November 2013

Location: Australian Museum, Indigenous Australians: Australia’s First Peoples gallery

We're hosting four days of Indigenous cultural experience and interactions in our Indigenous Australians gallery. Our program aims to engage and educate audiences about Aboriginal heritage and culture, particularly in regards to NSW.

Come along for an opportunity to interact with Indigenous artists and cultural practitioners as they interpret objects and share insights into their cultures.

Talks

$20 each (bookings essential – click the links below)We're hosting four talks on Indigenous Australian culture, beliefs, heritage and history:

- The Native Institute – Karla Dickens and Leanne Tobin

Sunday 17 November

11.00am – 12.30pm - The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia – Bill Gammage AM

Sunday 17 November

2.00pm – 3.30pm - Aboriginal Astronomy – Ray Norris

Tuesday 19 November

Time 11.00am – 12.30 pm - Connections: Dreaming stories and the rock art of Southern Sydney – Les Bursill OAM

Tuesday 19 November

Time 2.00pm – 3.30 pm

↧

↧

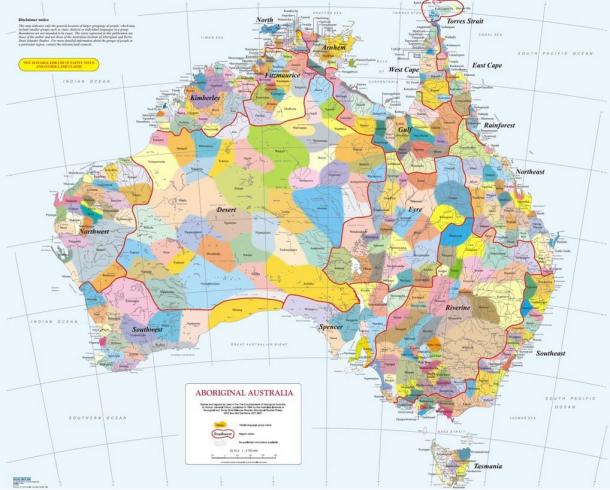

Exploring Astronomical Knowledge and Traditions in the Torres Strait: A Project Supported by the Australian Research Council

In previous posts, we explored aspects of cultural astronomy in the Torres Strait. The indigenous people of these islands have a culture based on astronomy, yet the last major work on Islander astronomy was published in 1907. And even then the author clarified that his study was grossly incomplete. In the 1993 book "Stars of Tagai" by Nonie Sharp (Aboriginal Studies Press), she explained how Islander people were guided by Tagai - who is seen as a large constellation stretching from the Southern Cross to Corvus, down to Scorpius. Although the book contains important astronomical information, it is not about Islander astronomy and it does not shed light on Islander knowledge relating to the Milky Way, Magellanic Clouds, sun, moon, any of the planets, or other astronomical phenomena.

This left a gap in our knowledge about cultural astronomy in the Torres Strait. Dr Duane Hamacher, a Lecturer in the Nura Gili Indigenous Programs Unit at the University of New South Wales, realised the importance of this work and the fact that Islander staff at Nura Gili have close connections with their home country. In March 2013, he applied for a research grant through the Australian Research Council called the Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DECRA). This highly competitive grant is designed to support researchers who are in the early stages of their academic careers (within 5 years of being awarded a PhD).

Dr Hamacher was successful and was awarded a DECRA to study Islander astronomy. The grant, worth $350,000, will cover the project over a period of three years.

Project Description: The astronomical knowledge of Indigenous people across the world has gained much significance as scientists continue to unravel the embedded knowledge in material culture and oral traditions. As social scientists gain a stronger role in emerging scholarship on Indigenous astronomy, growing evidence of celestial knowledge is being rediscovered in artefacts, iconography, document archives, literature, folklore, music, language and performances. This project seeks to investigate an underexplored area of astronomical knowledge in Australia. It will be the first comprehensive study of the astronomical traditions of Torres Strait Islanders and will add to the growing body of knowledge regarding Indigenous astronomy.

This project will involve surveying over 1500 published documents on Islander culture, exploring archival documents in libraries, studying artefacts and artworks in museums across Australia and Europe, and conducting ethnographic fieldwork in the Torres Strait. This is where Dr Hamacher will live with Islander communities to learn firsthand from elders about their astronomical knowledge and practices. See the video below about current efforts to explore and record Islander astronomy in the Torres Strait.

↧

New University Course on Indigenous Astronomy

A new university course on Indigenous Astronomy will be taught at the University of New South Wales for the first time during Semester 1, 2014. The 3rd year course (ATSI 3006: Astronomy of Indigenous Australians) is worth 6 units of credit and is part of the new major in Indigenous Studies through the Nura Gili Indigenous Unit. It is one of 5 new courses on Indigenous Studies being developed for 2014. The new Indigenous Studies major was developed as a new way of teaching Indigenous Studies, which focuses on three themes:

- 'Continuities' show the ways in which Indigenous people use their traditional knowledge and cultural systems to sustain their communities today;

- 'Convergences, Ruptures, and Discontinuities' provide students with a variety of theoretical approaches for understanding the impact of colonisation on Indigenous peoples and communities;

- 'Navigating the Interface' enables students learn and appreciate the complexities of knowledge production in Indigenous cultures.

|

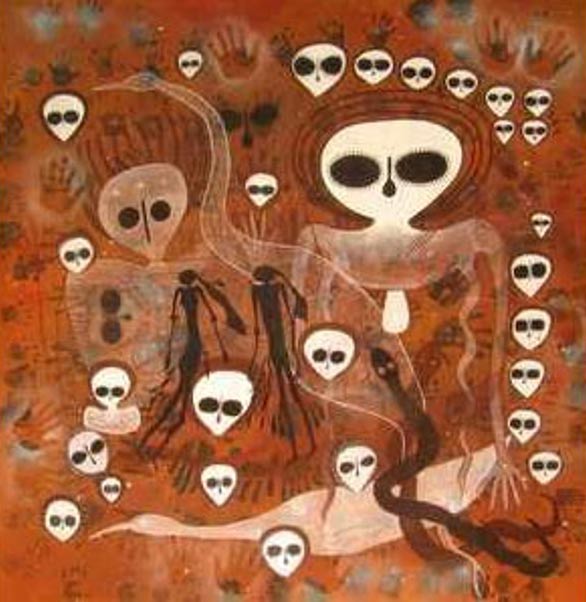

| Image by Paul Curnow and Gail Glasper. |

ATSI 3006 focuses on the ways in which astronomical knowledge is developed, utilised, and encoded in the oral traditions and material culture of Indigenous peoples, with a focus on Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders. This course will introduce students to the growing inter-discipline of cultural astronomy and explore the astronomical knowledge and traditions of Indigenous Australians. Students will learn about the history, development, theory, and methods of cultural astronomy, followed by a conceptual (non-mathematical) treatise of positional astronomy and celestial mechanics using the new state-of-the-art planetarium at Sydney Observatory. Students will then explore the myriad ways in which the sun, moon, and stars inform and guide Indigenous practices such as navigation, calendar development, and food economics, as well as social structure, including customs, laws, kinship structure, and marriage/totem classes.

|

| "Milky Way" bark painting by Mawalan Marika from Yirrkala, NT (1963). Australian Museum collection. |

The teaching method is not focused on lecturing. Instead, short lectures will be followed by in-class activities, discussion groups, and field trips. Assessments are based on in-class activities, a research project, and an industry project. The latter involves working with a curator, astronomer, or educator to develop educational materials, curate an exhibit, develop an Indigenous astronomy program for a planetarium/observatory, or produce a media/art exhibit.

Students will also learn about opportunities to continue their study of Indigenous Astronomy through an Honours, Masters, or Doctoral program at UNSW.

|

| Yuin elder Uncle Paul McLeod (right) teaches Nura Gili students about traditional ecological knowledge at Jervis Bay. Photo by D. Hamacher. |

But what if I am not majoring in Indigenous Studies - can I still take the course?

YES!

The course is available as a General Education unit (GenEd), meaning *any* student at UNSW that is eligible to enrol in a 3rd year course - regardless of their major - can take the subject, including foreign exchange and study abroad students.

About the Course Conveynor

|

| Duane and Uncle Paul. |

The course was developed, and will be taught, by Dr Duane Hamacher. Duane is a Lecturer and ARC Discovery Early Career Researcher at Nura Gili, specialising in Indigenous astronomy. Born and raised in the United States, he graduated with a degree in physics from the University of Missouri before moving to Sydney to complete a Masters degree in astrophysics at UNSW. He then earned a PhD in Indigenous Studies from Macquarie University with a thesis on Aboriginal Astronomy. Duane worked as an astronomy educator at Sydney Observatory for five years and is now a consultant curator. He has a passion for teaching and hopes to make this course one of the most engaging, interesting, and enjoyable courses students will have during their degree program.

Queries: d.hamacher@unsw.edu.au

↧

Charcoal Night: Re-Imagining the Night Sky

'Charcoal Night' - is a short film documentary about re-imagining the night sky, created in partnership with students from the Albury Wodonga Community College, the Astronomical Society of Albury Wodonga (ASAW) and Murray Arts. The documentary was shown at various high profile venues across the Albury/Wodonga region during National Science Week. This project was made possible with a NSW Inspiring Science Australia Grant.

↧

↧

Bora Ceremonial Grounds and the Milky Way: a Connection?

By Robert Fuller and Duane Hamacher

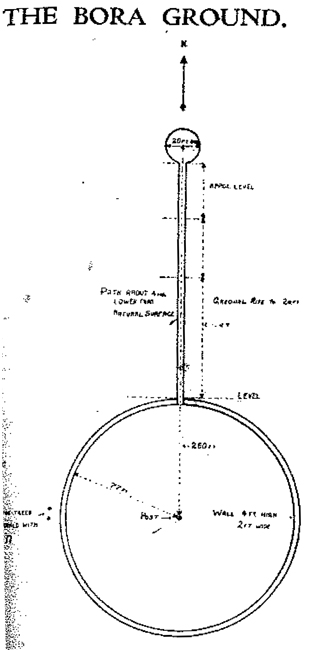

Most Aboriginal language groups in Australia practised initiation ceremonies. In some places, this tradition continues. During this ceremony, teenage boys were taken through a rite of passage, where they would perfectly recite the stories, laws, and customs they were taught, and perform the dances with extreme precision among other things (Figure 1). The initiation also involved a form of body modification, but most of these details are considered secret. This ceremony proved to their elders that they were ready to be men. In southeastern Australia, it was generally known as a Bora ceremony, taken from the Kamilaroi term for the word. The Bora ceremony was commented upon by the earliest European arrivals in Sydney. One of the first Bora sites identified was at Farm Cove in Sydney – what is now the Botanic Gardens near the Opera House.

|

| Figure 1: Photograph of a Bora ceremony, taken in 1898 by Charles Kerry. National Library of Australia |

Most Bora grounds have a distinct shape. They tend to consist of two rings of flattened earth, with an embankment of raised earth or stones, and a pathway connecting them. One is a larger “public” circle, where women and other people can attend. The other is a smaller sacred circle, which is considered sacred and secret. This is where the final part of the initiation and body modification takes place. Secret parts of the ceremony are not discussed out of respect to the Aboriginal elders.

|

Figure 2: Casino Bora Ground, Richmond Valley, NSW. Image from Sandra Bowdler (2000). A heritage study of Indigenous ceremonial (Bora) sites. University of Western Australia, Perth. |

Bora ceremonies take place between August and the following March, which are the summer months. The ceremonial grounds are often laid out long before the ceremony is held, or even renewed from previous ceremonies. Although Bora ceremonies were held at any time over this long period, it seems many of them were held in August and September. And this may have astronomical significance.

It seems the Bora ceremony is connected to the Emu in the Sky. The Emu in the Sky is a spirit emu found in the Milky Way (Figure 3). This Aboriginal constellation is not made up of bright stars, but instead comprises dark patches in the Milky Way, stretching from the Coalsack Nebula near the Southern Cross down to the centre of the galaxy in Scorpius. Since male emus brood, hatch, and rear the emu chicks, it is symbolic of the initiation of adolescent boys by their male elders. In southeast Australia, the culture hero Baiame is believed to live behind the Milky Way. The son of Baiame, is a being called Daramulan, who watches over, and even comes down from the sky for, the Bora ceremony, and his wife is an emu.

|

Figure 3: The Emu in the Sky. Image from http://www.abc.net.au/science/starhunt/tour/virtual/coalsack/ |

One elder said that the Bora ceremonial ground was reflected in the Milky Way as the Sky Bora: two dark patches within the Milky Way that mimic the two earthly Bora circles (Figure 4). These dark patches are also within the celestial emu: the larger one is the Coalsack (the Emu’s head) and the other is down the Milky Way towards the Emu’s body. As it turns out, August and September is when the Milky Way is vertical above the south-southwest horizon in the evening sky. Because of this connection, the researchers – Robert Fuller (Macquarie University), Dr Duane Hamacher (University of New South Wales), and Professor Ray Norris (CSIRO/Macquarie University) – wondered if the Bora ceremonial grounds were oriented to the direction of the Sky Bora/Emu in the Sky when Bora ceremonies were held. Information collected by anthropologists learning from Aboriginal elders suggested as much, but Fuller, Hamacher, and Norris needed to demonstrate this.

|

Figure 4: the Sky Bora in the Milky Way at the time of year ceremonies were held (evenings in August and September). Image made by R.S. Fuller using Stellarium. |

Fuller and his colleagues collected data for 1,170 Bora grounds in New South Wales and southeastern Queensland. They identified 68 Bora grounds that contained clear information about the site’s orientation, from the large circle to small circle (mostly within 200 km of Brisbane). The 68 sites showed that a significant number of them were oriented to the southern quadrant – more so than any other direction (and by quite a bit more!).

This is interesting, but could these results be a product of chance? To test this hypothesis, the researchers used a statistical technique called a Monte Carlo simulation. This is where random orientations, like those of the Bora grounds, were simulated millions of times over. If these orientations were common, the simulation would confirm that. The researchers ran the simulation 100 million times. Only 303 of the simulations gave a result like the one found by Fuller and his colleagues. This means the probability of these orientations occurring by chance is one in 3 million, or 0.0003%! This confirms that there is definitely a preference for Bora grounds to be oriented towards the south. This coincides with the position of the Milky Way in the evening sky during August and September.

Is this conclusive proof that Bora ceremonial grounds were oriented to the position of the Milky Way in August and September? No. But it takes us one step closer to finding out. Fuller and his colleagues are currently working with elders across NSW to learn more about the Bora ceremony and its connection to the sky, which is starting to reveal new and interesting facts about this initiation ceremony.

To learn more about the research, check out the paper “Astronomical Orientations of Bora Ceremonial Grounds in Southeast Australia.” Australian Archaeology, No. 77, pp. 30-37.

- Read the published paper here (requires payment through journal)

- Read the preprint here (free)

↧

The First Astronomers: Education in the Pilbara

by Dr Andi Horvath

As Australia has the oldest continuous culture on Earth, the first Australians were very likely to have also been the first astronomers. In 2008 CSIRO astrophysicist Ray Norris set out with wildlife expert Cilla Norris to learn, collect and document the stories of Australian Aboriginal astronomy from community elders who were the custodians of these stories.

There are hundreds of different Aboriginal cultures, and therefore as many different stories about the night skies. Some have been lost since colonisation and some were sacred, private knowledge. One thing was universal: Indigenous Australians valued the sun, moon and stars for information about seasonal survival, but also for its keeping of culture and story.

There are hundreds of different Aboriginal cultures, and therefore as many different stories about the night skies. Some have been lost since colonisation and some were sacred, private knowledge. One thing was universal: Indigenous Australians valued the sun, moon and stars for information about seasonal survival, but also for its keeping of culture and story.

Ray and Cilla Norris’s publication "Emu Dreaming: An introduction to Australian Aboriginal Astronomy" became the message stick to a new generation of teachers, who are now adding the richness of Indigenous observations to astronomy science classes.

Astrophysicist Alan Duffy is one who, after being introduced to concepts of Indigenous astronomy, will never look at the Milky Way the same way again. And after visiting the Pilbara earlier this year to share his knowledge about Indigenous astronomy with students in both Indigneous and non-Indigenous schools, he is even more encouraged, with new knowledge, and optimism about the future of astronomy in Australia.

Dr Duffy’s invitation to visit schools in the Pilbara to share his love of astronomy came about as part of Pilbara Joblink and the Federal Government’s ‘Inspiring Australia’ initiative called the ‘Science career carousel’. Dr Duffy visited Karratha High School, St Luke’s College and Roeburne, a Year 6 to 9 Indigenous school.

“I initially felt awkward about being the Irish boy from the Emerald Isle who visits the red regions of the Pilbara to talk to Indigenous kids about their own ancestral knowledge,” he says. “As there is a huge variety of Indigenous stories from different regions of Australia I decided to share the ones I knew in the fine oral tradition of storytelling.”

Dr Duffy explained to the students that Indigenous astronomy is a great example of how sophisticated Aboriginal science and culture was through its development. He also explored the fundamental difference in the way traditional European astronomy conceives the constellations by connecting the dots of stars to form pictures attributed to Greek mythology, whereas Aboriginal astronomy connects not just the stars but also the black spaces in-between. Two different ways of viewing the same night’s sky!

“The school kids were very excited by the “emu in the sky” which stretches out in what European astronomers call the Milky Way,” he says. “Once you see it, you can never look at the Milky Way the same way again. As a constellation, it is far more convincing than the obscure European pictures.

“There is an engraving of the emu in the sky in stone at Ku-ring-gai Chase national park just north of Sydney, where the Guringai people lived until the British arrived in 1788, and the time of year when the emu rises just above the horizon is also the season when real emus lay their eggs; it has remarkable timekeeping accuracy. This knowledge is important to survival, especially if you were keen on a fresh egg for dinner.”

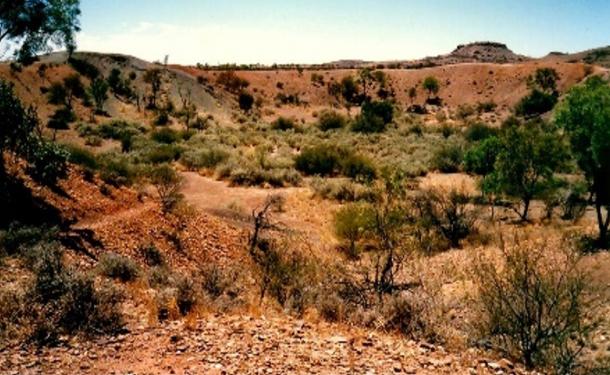

Dr Duffy also explains that stretches of the Pilbara resemble the Martian landscape more than any other on Earth, and have been used by NASA to test and train their Mars rovers.

He found the red terrain fascinating and beautiful, and was not immune to the irony that during sessions students were enjoying a NASA app allowing them to simulate driving the Mars rover on Martian landscapes created from the very place they lived and learned.

Dr Duffy says he was amazed by how much he had learnt from visiting these students in the Pilbara.

“I spoke to the students about Indigenous astronomy, on using the sky as a ‘GPS’ and a calendar. I had no idea until I had done the research that the European story of Orion the Hunter (who is upside down in Australia) chasing seven sisters (a cluster of seven stars) is essentially the same story in Indigenous astronomy where a fisherman hunter and his three brothers are also chasing the seven sisters. I agree with Ray and Cilla Norris this suggests the possibility that these stories may have come from one set of people a very long time ago.”

Dr Duffy says one the most memorable student questions during his time in the outback also revealed complex analysis of physical concepts in astronomy.

“A girl asked, if the sun is so hot why is space so cold? While the answer is simple the question is wonderfully complex. The simple answer is, just as we walk further and further away from a campfire the energy is less and it feels cold in the next paddock. But the question is beautiful, Einstein would be proud, because there is logic in the observation that is embedded in the question. Consider the notion that it takes time for a room (our planet) to heat up. It suggests there was a time when the sun did not shine but now it does. It suggests there must have been a beginning to the universe.”

Dr Duffy laughs at himself and reiterates “I’m the Irish boy from the Emerald Isle who visits the red regions of the Pilbara to remind them of what they already know. That is, the universe is a fascinating story any way you look at it.

“Learning from the elders in any culture has allowed for knowledge and know-how to be passed down the generations. Their stories have helped us make sense of the world, navigate our lives and celebrate annual rituals,” he says.

This article was first published through The Age on 13 January 2014.

Read the original article here: http://www.theage.com.au/national/education/voice/the-first-astronomers-20140106-30cx6.html#ixzz2qtfgbXxD

↧

Maps By Night: Indigenous Navigation

On Friday 24 January 2014, Professor Ray Norris gave a talk on Aboriginal astronomy and navigation at the National Library of Australia in Canberra.

In Australian Aboriginal cultures, mental maps are built on songs and ceremony. These songlines and other navigational tools enabled Aboriginal Australians to navigate across the country, trading artefacts and sacred stories. Join Ray Norris as he discusses how Indigenous people used stories and other navigational tools to cross country.

Click on the bark painting above to access the audio file (mp3).

↧

Indigenous Astronomy @ UNSW

Australia’s Indigenous people have rich and ancient traditions relating to the stars, which informed social practices, sacred law, and ceremony, and were used for navigation, calendars, hunting, fishing, and gathering.

The Nura Gili Indigenous Programs Unit at the University of New South Wales in Sydney is the national leader in teaching and research in this area and our program is dedicated to increasing our understanding of the intricate and complex ways in which astronomical knowledge is encoded in oral traditions and material culture. We have staff, students, and educators teaching, researching, and sharing various aspects of Indigenous astronomical knowledge with the public.

Our Teaching

Dr Duane Hamacher developed new undergraduate courses on Indigenous Science and Indigenous astronomy for Nura Gili. The units are part of the Indigenous Studies major and are available to all UNSW students as General Education units. Both courses are taught by Dr Hamacher in Semester 1 of each year. International exchange and study abroad students from any academic background are encouraged to enroll.

- ATSI 2015: The Science of Indigenous Knowledge: Explore the various ways in which scientific information is encoded within traditional Indigenous knowledge systems, including astronomy, weather and climate, ecology, bush medicines, mathematical systems, geological events, and fire practices. Guest speakers, including academics and elders, bring a unique perspective the course, which uses an interactive "inverted classroom" approach.

- ATSI 3006: The Astronomy of Indigenous Australians: Learn about the ways in which Indigenous understood and utilised the stars in an interactive classroom environment, develop your knowledge of naked-eye astronomy in Sydney Observatory's digital planetarium. and conduct original research and use your findings to create a planetarium show, curate an exhibit, produce educational materials, or film a documentary.

Our Research

Research at Nura Gili covers a range of projects on Indigenous astronomy. We work closely with Aboriginal and Islander communities, educators, and industry partners, and collaborate with researchers and teams at Macquarie University, Curtin University, and Griffith University. Some of our research projects are as follows:

Rediscovering Indigenous Astronomical Knowledge

Professor Martin Nakata and Dr Duane Hamacher are leading a collaboration with UNSW’s School of Computer Science & Engineering, Microsoft Research, and the State Library of New South Wales, to develop a public online repository for astronomical knowledge accessible to Indigenous communities worldwide, with additional information sourced from institutions and collections. Martin is also working closely with UNSW’s College of Fine Arts (COFA) to produce cutting-edge visual technologies for presenting this knowledge.

Exploring Astronomical Knowledge and Traditions in the Torres Strait

Dr Duane Hamacher was awarded a major grant from the Australian Research Council to study Torres Strait Islander astronomy. The purpose of this study is to chart Torres Strait Islander customs and traditions with a deep connection to the sun, moon, and stars. A well-researched and documented library of astronomical knowledge will help Islanders continue longstanding traditions in developing knowledge about their place in the world.

Wiradjuri Skies: Aboriginal Astronomy in central NSW

Trevor Leaman is conducting his PhD research on the astronomical knowledge and traditions of the Wiradjuri people of NSW. This project will see Trevor conducting ethnographic research with communities across the Central West of NSW. The project will expand our knowledge of Wiradjuri astronomy and provide educational materials for the community.

Aboriginal Astronomy in the Hunter Region of NSW

Emma McDonald is researching the astronomy of the Worimi, Awabakal, and Wonnarua people of the Hunter region, NSW for a BSc with Honours degree. Emma will study ethnohistoric records, archival documents, and museum artefacts to better understand the role of astronomy in these Aboriginal communities.

Aboriginal Astronomy, Environment, and Ecology

Plants, animals, and seasonal cycles were an important component of Indigenous astronomical traditions. This project examines the role animals and plants played in these traditions and how the stars informed the people of seasonal change, and the best times to hunt, fish, and gather.

ATSI 3006 Research Projects

Students enrolled in ATSI 3006 are undertaking small research projects on topics in Indigenous astronomy, including

- Aboriginal astronomy in the Sydney region

- Aboriginal astronomy in the Melbourne region

- Aboriginal astronomy in Tasmania

- Cultural astronomy in the Torres Strait

- Yuin Aboriginal astronomy (south coast NSW)

- Music, culture, and astronomical traditions

- Calendars and astronomy

- Astronomical symbolism in material culture

Our Team

Duane is an American and earned degrees in astrophysics and Indigenous studies, with a PhD thesis on Aboriginal astronomy. He joined Nura Gili staff to develop teaching and research programs in Indigenous astronomy and was awarded an ARC grant to study the astronomy of Torres Strait Islanders. He is also a consultant curator and astronomy educator at Sydney Observatory.

Professor Martin Nakata

Professor and Director of Nura Gili

Martin is an Indigenous Torres Strait Islander and the first Islander to earn a PhD in Australia. He is a national leader in Indigenous education and Indigenous knowledge, and published the book Disciplining the Savages - Savaging the Disciplines. He leads a project with Microsoft Research and the Mitchell Library to capture and record Indigenous astronomy for the WorldWide Telescope.

Professor and Director of Nura Gili

Martin is an Indigenous Torres Strait Islander and the first Islander to earn a PhD in Australia. He is a national leader in Indigenous education and Indigenous knowledge, and published the book Disciplining the Savages - Savaging the Disciplines. He leads a project with Microsoft Research and the Mitchell Library to capture and record Indigenous astronomy for the WorldWide Telescope.

Trevor Leaman

PhD Candidate (FASS – Environmental Humanities)

Trevor is researching the astronomy of the Wiradjuri people of central NSW under the supervision of Dr Hamacher. His Masters degree involved studying the astronomy of Aboriginal communities near Ooldea, South Australia. He earned degrees and diplomas in biology forestry, engineering, and astronomy, and is an astronomy educator at Sydney Observatory.

PhD Candidate (FASS – Environmental Humanities)

Trevor is researching the astronomy of the Wiradjuri people of central NSW under the supervision of Dr Hamacher. His Masters degree involved studying the astronomy of Aboriginal communities near Ooldea, South Australia. He earned degrees and diplomas in biology forestry, engineering, and astronomy, and is an astronomy educator at Sydney Observatory.

Emma McDonald

Honours Student (BEES – Environmental Science)

Honours Student (BEES – Environmental Science)

Emma is an Aboriginal Worimi woman from Port Stephens, NSW. She earned a degree in geology (with a minor in Aboriginal studies) and is pursuing an Honours project on the astronomy of Aboriginal communities in the Hunter region of NSW under the supervision of Dr Hamacher. She also works as a Discovery Ranger for National Parks & Wildlife.

Tui Britton

Consultant Science Communicator

Consultant Science Communicator

Tui is a Maori descendent of the Ngapuhi iwi of northern New Zealand. She was born in Christchurch and educated in Singapore, England, America, and Australia. She earned degrees in astrophysics and is finishing a PhD in radio astronomy. Tui produces educational units and writes popular articles and books on Indigenous astronomy and astrophysics. She is also an astronomy educator at Sydney Observatory

You?!![blank]()

You?!

We welcome passionate students wishing to enrol in our undergraduate units or pursue research projects for an Honours, Masters, or Doctoral degree. Interested parties should contact Dr Duane Hamacher. A list of potential projects and degree information can be found here.

↧

↧

The Kamilaroi and Euahlayi Emu in the Sky

The concept of the Emu in the Sky exists in different Aboriginal groups across Australia. These stories have different meanings, from indicators of resources (when to collect emu eggs) to that of culture heroes. The Kamilaroi and Euahlayi peoples, who live in the north and northwest of New South Wales, also have traditions of an Emu in the Sky, which differed from many of the other accounts. For the Kamilaroi and Euahlayi, the celestial Emu represents different things at different times of the year. The Emu first becomes visible in March. When it is fully visible in the Milky Way during April and May, it assumes the form of a running emu (Figure 1). This represents a female emu chasing the males during the mating season. Because emus begin laying their eggs at this time, this appearance of the celestial Emu is a reminder that the emu eggs are available for collection.

|

| Figure 1 |

In June and July, the appearance of the Emu changes, as the legs disappear. The Emu, which is now male, is sitting on its nest, incubating the eggs (Figure 2). The eggs are still available for collection as a resource at this time.

|

| Figure 2 |

The Kamilaroi and the Euahlayi have in common their male initiation ceremony, called the bora. The preferred time for the bora ceremony is during the summer, but the planning for the ceremonies, and possibly the layout of the bora site, may take place in August and September. There is a strong connection between the bora ceremony and the Milky Way, where the culture hero Baiame lives, and to whom the ceremony is dedicated. There is also evidence that the Emu is connected to the ceremony: as male emus rear the young, so male Aboriginal elders nurture the young initiates into manhood.

The bora ceremonial site usually consists of two circles, one large, and one small, connected by a pathway. In August and September, the Emu once again changes appearance to that of two circles in the sky, vertically aligned above the south-southwest horizon (Figure 3). This is the direction to which most bora sites are aligned (from large circle to small circle).

|

| Figure 3 |

Later in the year, around November, the Emu once again changes appearance and becomes Gawarrgay/Gawarghoo, a featherless Emu that travels to waterholes and looks after everything that lives there. The Emu is now low on the horizon in the evening, so it appears only as the “body” of the Emu. The Kamilaroi and Euahlayi say this is because the Emu is sitting in a waterhole (Figure 4). As a consequence, the waterholes in country are full (which is often the case in November).

|

| Figure 4 |

Later in the summer, the Milky Way and the Emu dip below the horizon. This signifies that the Emu has left the waterholes, which dries up the waterholes.

The Kamilaroi and Euahlayi peoples have a complete story of the Emu in the Sky, and this reflects their belief that, at one time, the sky and everything in it was “down here”, and what is now “down here” was in the sky. This explains the connection between the Emu in the Sky, and the emu bird on the ground, and the connections to resource management and the ceremonial aspects of the male initiation ceremony.

This post is based on research conducted by Robert Fuller, Michael Anderson, Ray Norris, and Michelle Trudgett with Kamilaroi and Euahlayi elders and custodians. Their paper, “The Emu SkyKnowledge of the Kamilaroi and Euahlayi Peoples” will appear in the July 2014 issue of the Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage (Volume 17, Issue 2). You can read a preprint of the paper here.

↧

"Cultural Astronomy Channel" - YouTube

The Cultural Astronomy Channel is a YouTube channel moderated by Prof Jarita Holbrook from the University of the Western Cape in Cape Town, South Africa.

The channel features a number of videos on the subject of cultural astronomy. Most recently, Prof Holbrook uploaded talks from the recent conference of the International Society of Archaeoastronomy and Astronomy in Culture in Cape Town (aka "Oxford X"). The theme of the meeting was "Astronomy, Indigenous Knowledge, and Interpretation" and featured a number of talks on Indigenous astronomy from around the world.

You can view videos here, including those from Cape Town. Updated versions of the talks that incorporate lecture slides will be uploaded in the future. A talk on Australian Indigenous astronomy is given by Dr Duane Hamacher.

↧

Are supernovae recorded in Indigenous astronomical traditions?

New research by Dr Duane Hamacher at the University of New South Wales explores Indigenous traditions that may describe supernovae, and sets criteria for confirming supernovae in oral tradition and material culture (e.g. artefacts, rock art, etc).

Hamacher, D.W. (2014). Are supernovae recorded in Indigenous astronomical traditions?

Journal of Astronomical History & Heritage, Vol. 17(2), pp. 161-170.

Abstract

Novae and supernovae are rare astronomical events that would have had an influence on the sky-watching peoples who witnessed them. Although several bright novae/supernovae have been visible during recorded human history, there are many proposed but no confirmed accounts of supernovae in indigenous oral traditions or material culture. Criteria are established for confirming novae/supernovae in oral traditions and material culture, and claims from around the world are discussed to determine if they meet these criteria. Aboriginal Australian traditions are explored for possible descriptions of novae/supernovae. Although representations of supernovae may exist in Aboriginal traditions, there are currently no confirmed accounts of supernovae in Indigenous Australian oral or material traditions.

|

| Image from http://www.bosssupernova.com/whatisasupernova.htm |

↧

Stories from the sky: astronomy in Indigenous knowledge

by Duane Hamacher (University of New South Wales)

Indigenous Australian practices, developed and honed over thousands of years, weave science with storytelling. In this Indigenous science series, we’ll look at different aspects of First Australians' traditional life and uncover the knowledge behind them – starting today with astronomy.

This article contains the names of Aboriginal people who have passed away.

Indigenous Australians have been developing complex knowledge systems for tens of thousands of years. These knowledge systems - which seek to understand, explain, and predict nature - are passed to successive generations through oral tradition.

As Ngarinyin elder David Bungal Mowaljarlai explains: “Everything under creation […] is represented in the ground and in the sky.” For this reason, astronomy plays a significant role in these traditions.

Western science and Indigenous knowledge systems both try to make sense of the world around us but tend to be conceptualised rather differently. The origin of a natural feature may be explained the same in Indigenous knowledge systems and Western science, but are couched in very different languages.

A story recounted by Aunty Mavis Malbunka, a custodian of the Western Arrernte people of the Central Desert, tells how long ago in the Dreaming, a group of women took the form of stars and danced a corroboree (ceremony) in the Milky Way.

One of the women put her baby in a wooden basket (coolamon) and placed him on the edge of the Milky Way. As the women danced, the baby slipped off and came tumbling to Earth. When the baby and coolamon fell, they hit the ground, driving the rocks upward. The coolamon covered the baby, hiding him forever, and the baby’s parents – the Morning and Evening Stars – continue to search for their lost child today.

If you look at the evening winter sky, you will see the falling coolamon in the sky, below the Milky Way, as the arch of stars in the Western constellation Corona Australis – the Southern Crown.

The place where the baby fell is a ring-shaped mountain range 5km wide and 150m high. The Arrernte people call it Tnorala. It is the remnant of a giant crater that formed 142 million years ago, when a comet or asteroid struck the Earth, driving the rocks upward.

Predicting seasonal change

When the Pleiades star cluster rises just before the morning sun, it signifies the start of winter to the Pitjantjatjara people of the Central Desert and tells them that dingoes are breeding and will soon be giving birth to pups.

The evening appearance of the celestial shark, Baidam traced out by the stars of the Big Dipper (in Ursa Major) tells Torres Strait Islanders that they need to plant their gardens with sugarcane, sweet potato and banana.

When the nose of Baidam touches the horizon just after sunset, the shark breeding season has begun and people should stay out of the water as it is very dangerous!

Torres Strait Islanders' close attention to the night sky is further demonstrated in their use of stellar scintillation (twinkling), which enables them to determine the amount of moisture and turbulence in the atmosphere. This allows them to predict weather patterns and seasonal change. Islanders distinguish planets from stars because planets do not twinkle.

In Wergaia traditions of western Victoria, the people once faced a drought and food was scarce. Facing starvation, a woman named Marpeankurric set out in search of tucker for the group. After searching high and low, she found an ant nest and dug up thousands of nutritious ant larvae, called bittur.

This sustained the people through the winter drought. When she passed away, she ascended to the heavens and became the star Arcturus. When Marpeankurric rises in the evening, she tells the people when to harvest the ant larvae.

In each case, Indigenous astronomical knowledge was used to predict changing seasons and the availability of food sources. Behind each of these brief accounts is a complex oral tradition that denotes a moral charter and informs sacred law.

An important thing to consider is that small changes in star positions due to stellar proper motion(rate of angular change in position over time) and precession (change in the orientation of Earth’s rotational axis) means that a few thousand years ago, these sky/season relationships would have been out of sync.

This means knowledge systems had to evolve over time to accommodate a changing sky. This shows us that what we know about Indigenous astronomical knowledge today is only a tiny fraction of the total knowledge developed in Australia over the past 50,000-plus years.

Moving forward

As we increase our understanding of Indigenous knowledge systems, we see that Indigenous people did develop a form of science, which is used by Indigenous and non-Indigenous people today.

Traditional fire practices are used across the country, bush medicines are being used to treat disease, and astronomical knowledge is revealing an intellectual complexity in Indigenous traditions that has gone largely unrecognised.

It is time we show our appreciation for Indigenous knowledge and celebrate the many ways we can all learn from this vast accumulation of traditional wisdom.

Duane is speaking at The Edges of Astronomy symposiumat the Australian Academy of Science in Canberra on December 4, 2014.

↧

↧

Studying Cultural Astronomy for a Career - a Guide

By Duane Hamacher

I am frequently asked about how one can go about studying cultural astronomy and possibly pursue a career in the field. Due to its interdisciplinary nature, knowing what to study and how to build a foundation in this area is not as straightforward as one might think.

This blog post will serve as a guide to studying cultural astronomy at the university level, from undergrad to PhD. I will also list some of the career options for graduates in this field. This is based on my knowledge and experience.

What is Cultural Astronomy?

Cultural astronomy is generally divided into two sub-disciplines: archaeoastronomy and ethnoastronomy.

I am frequently asked about how one can go about studying cultural astronomy and possibly pursue a career in the field. Due to its interdisciplinary nature, knowing what to study and how to build a foundation in this area is not as straightforward as one might think.

This blog post will serve as a guide to studying cultural astronomy at the university level, from undergrad to PhD. I will also list some of the career options for graduates in this field. This is based on my knowledge and experience.

What is Cultural Astronomy?

Cultural astronomy is the academic study of the ways in which various cultures understood and utilized the celestial realm. It is a social science informed by the physical sciences. Since it involves human perception of the natural world, it is grounded in the social sciences. But as it utilises information and knowledge about the natural world, it is informed by the physical and natural sciences.

Cultural astronomy is generally divided into two sub-disciplines: archaeoastronomy and ethnoastronomy.

Archaeoastronomy is the study of the astronomical practices and beliefs of past cultures. It relies heavily on the archaeological record and has traditionally focused on alignments in monuments, structures, and stone arrangements. This approach relies heavily on archaeological surveys, precision measurements, and statistical analysis.

|

Archaeoastronomical studies at Chankillo in Peru. |

Ethnoastronomy is the study of the astronomical practices and beliefs of contemporary cultures, with a focus on Indigenous peoples. It relies heavily on the the ethnographic and historical records and involves learning about human understanding of the sky directly from the people themselves, particularly Indigenous elders.

The study of astronomy in culture is a growing field of interest, and an increasing number of masters and doctoral degrees are being awarded with theses and dissertations in the field. The graph below shows the increase trend in graduate degrees with theses/dissertations in cultural astronomy being awarded between 1965 and 2004 (McCluskey, 2004).

Cultural astronomy is highly interdisciplinary, so could consider a number of different majors and degree programs, depending on your personal interests. If you want to learn about astronomical alignments in temples, megalithic structures, or ancient cities, archaeoastronomy is your area and archaeology and classics are suitable fields of study. If you are interested in learning about contemporary Indigenous cultures, anthropology and sociology are a better option. If your interest lies in interpreting ancient texts, linguistics and languages would be a suitable option.

Very few universities have any structured programs in cultural astronomy, and only a handful offer courses on the subject (a list of such courses will be the focus of a future post). So do not expect to find a university where you can complete a full program in cultural astronomy... you'll have to build your own.

|

Ethnoastronomical work with Aboriginal elder Bill Yidumduma Harney. |

The study of astronomy in culture is a growing field of interest, and an increasing number of masters and doctoral degrees are being awarded with theses and dissertations in the field. The graph below shows the increase trend in graduate degrees with theses/dissertations in cultural astronomy being awarded between 1965 and 2004 (McCluskey, 2004).

|

| Dissertations and Theses in Cultural Astronomy (1965-2004) |

Cultural astronomy is highly interdisciplinary, so could consider a number of different majors and degree programs, depending on your personal interests. If you want to learn about astronomical alignments in temples, megalithic structures, or ancient cities, archaeoastronomy is your area and archaeology and classics are suitable fields of study. If you are interested in learning about contemporary Indigenous cultures, anthropology and sociology are a better option. If your interest lies in interpreting ancient texts, linguistics and languages would be a suitable option.

Very few universities have any structured programs in cultural astronomy, and only a handful offer courses on the subject (a list of such courses will be the focus of a future post). So do not expect to find a university where you can complete a full program in cultural astronomy... you'll have to build your own.

What should I study at the Undergraduate Level?

Regardless of which area of cultural astronomy you choose to pursue, you need a grounding in the social sciences, and a working knowledge of astronomy. Basic knowledge in other sciences, such as geology, ecology, and biology, are also useful. Skills such as surveying, computer programming, and statistics are also highly valuable. Majors or fields of study for each sub-discipline are given below. This is not an exhaustive list. It only serves as a general guide.

Archaeoastronomy: Archaeology, Anthropology, Ancient History, Classics, History & Philosophy of Science, Cultural Heritage Management. Note: knowledge of statistics and surveying are essential.

You would be best suited to take either a Major in a social science and a Minor in astronomy/physics, or double Major in both social science and astronomy/physics. A single major in the social sciences will not generally provide you with the scientific foundation necessary to work in the field, and vice versa for a major in the sciences. A dual Major or double degree will be very intensive but is the best overall option. A dual BA would be easiest (e.g. BA Anthropology/BA Astronomy). However, a BA/BS provides the widest breadth and opens up the most opportunities (e.g. BA Anthropology/BS Astronomy).

[A colleague at Macquarie University in Sydney completed a dual degree to pursue his interests in Egyptian astronomy. He completed a BA in Ancient History and a BS in Astrophysics, with an Honours year studying Egyptology. It was hard work, but he's glad he did it!]

What should I study at the Graduate/Postgraduate Level?

If you want to pursue a career in cultural astronomy, you will need to complete a PhD.

You will be best suited in a social science or humanities program. It is very important to carefully choose a university and department that will support the research, and a knowledgeable, able, and supportive supervisor. You also much carefully choose the field of study the degree in which the degree will be awarded. "Studies" programs tend to be more broad, while "traditional" programs (e.g. anthropology" are more narrowly focused.

PhDs in the sciences with a cultural astronomy thesis topic are rare. A study in 2004 showed that of 79 masters and doctoral degrees awarded with theses in some area of cultural astronomy, only 3 were awarded through physics/astronomy departments. This means you will be far more likely to be accepted into a PhD program through the social sciences than the physical sciences.

|

| Graduate degrees awarded with theses in cultural astronomy, divided into disciplines (1965-2004). |

Career Opportunities

It should be made very clear that cultural astronomy is a tiny academic field - only a handful of people in the world have managed to carve out a career in this discipline - and the chances of getting a job in that area are incredibly slim. That is the advice my supervisors gave me. But it is possible to study cultural astronomy and make a career out of it… I did. You simply have to carve a niche, strategise your career, and maximize your opportunities. Just remember that nothing is guaranteed and academia is brutally competitive.

There are also numerous employment opportunities that will utilize your skills and knowledge set, although the job may not entail further cultural astronomy research. These include:

- Research and/or Teaching Academic

- TAFE/Community College Instructor

- Cultural Heritage Management

- Archaeological and Anthropological Consultant

- Education and Curriculum Developer

- Museum or Gallery Curator

- Outreach Officer

- Astronomy Educator

- Tour Guide

- Tourism Consultant

- Media and Communication

- Journalism

- Policy Development

- Journal/Magazine Editor

- School Teacher

- Administration

- Park Ranger

- Technical Writer

- Analyst (for those with high maths/stats skills)

So if this is a subject you wish to pursue... go for it. But be warned that the chances of landing a career in the discipline are very small. But it is a very exciting field in which to work and provides you with broad skills that can be used in a number of careers.

↧

"Speaking with": Duane Hamacher on Indigenous astronomy

Duane Hamacher interviewed by Tamson Pietsch. Originally published on The Conversation on 19 December 2014, 11.35am AEDT.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander people have between 40,000 and 60,000 years of pre-colonial history that includes stories of constellations they observed in the night sky and traditions that align with the stars and the moon. But until recently, these stories were largely dismissed by the scientific community.

Researchers are now finding that Indigenous oral traditions contain vast environmental and scientific knowledge. These complex knowledge systems have helped Indigenous people survive Australia for tens of thousands of years.

Tamson Pietsch speaks with cultural astronomer Duane Hamacher about Indigenous astronomy and its complex relationship to history, culture and applied scientific knowledge.

↧

Finding meteorite impacts in Aboriginal oral tradition

Imagine going about your normal day when a brilliant light races across the sky. It explodes, showering the ground with small stones and sending a shock wave across the land. The accompanying boom is deafening and leaves people running and screaming.

This was the description of an incident that occurred over the skies of Chelyabinsk, Russia on February 15, 2013, one of the best recorded meteoritic events in history. This airburst was photographed and videoed by many people so we have a good record of what occurred, which helped explain the nature of the event.

But how do we find out about much older events when modern recordings were not available?

A century before Chelyabinsk, a similar event occurred on July 30, 1908, over the remote Siberian forest near Tunguska.

That explosion was even more powerful, flattening 80 million trees over an area of 2,000 square kilometres and sending a shock wave around the Earth – twice. It was 19 years before scientists reached the Tunguska site to study the effects of the blast.

The apparent lack of a meteorite fuelled speculation about how it formed, from sober suggestions of an exploding comet to more outlandish claims of mini-black holes and crashed alien spacecraft (research confirms it was an exploding meteorite).

Meteoric events in Indigenous oral tradition

In 1926, the ethnographer Innokenty Suslov interviewed the local Indigenous Evenk people, who still vividly remembered the Tunguska airburst.

At the time, a great feud persisted among Evenki clans. One clan called upon a shaman named Magankan to destroy their enemy. On the morning of July 30th, 1908, Magankan sent Agdy, the god of thunder, to demonstrate his power.

Many Indigenous cultures attribute meteoritic events to the power of sky beings. The Wardaman people of northern Australia tell of Utdjungon, a being who lives in the Coalsack nebula by the Southern Cross.

He will cast a fiery star to the Earth if laws and traditions are not followed. The falling star will cause the earth to shake and the trees to topple.

Like the Evenki, it seems the Wardaman have faced Utdjungon’s wrath before.

The Luritja people of Central Australia also tell of an object that fell to Earth as punishment for breaking sacred law. And we can still see the scars of this event today.

A surviving meteorite impact legend

Around 4,700 years ago, a large nickel-iron meteoroid came blazing across the Central Australian sky. It broke apart before striking the ground 145km south of what is now Alice Springs.

The fragments carved out more than a dozen craters up to 180 meters across with the energy of a small nuclear explosion.

Today, we call this place the Henbury Meteorites Conservation Reserve.

Aboriginal people have inhabited the region for tens-of-thousands of years, and it’s almost certain they witnessed this dramatic event. But did an oral record of this event survive to modern times?

When scientists first visited Henbury in 1931, they brought with them an Aboriginal guide. When they ventured near the site, the guide would go no further.

He said his people were forbidden from going near the craters, as that was where the fire-devil ran down from the sun and set the land ablaze, killing people and forming the giant holes.

They were also forbidden from collecting water that pooled in the craters, as they feared the fire-devil would fill them with a piece of iron.

The following year, a local resident asked Luritja elders about the craters. The elders provided the same answer and said the fire-devil “will burn and eat” anyone who breaks sacred law, as he had done long ago.

The longevity and benefits of oral tradition

The story of Henbury indicates a living memory of an event that occurred a few thousands of years ago. Might then we find accounts of events from tens of thousands of years ago?

Yes, it seems so.

Recent studies show that Aboriginal traditions accurately record sea level changes over the past 10,000 years.

Other studies suggest the volcanic eruptions that formed the Eacham, Euramo and Barrine crater lakes in northern Queensland more than 10,000 years ago are recorded in oral tradition.

In addition to demonstrating the longevity of Indigenous oral traditions, emerging research shows that these stories can lead to new scientific discoveries. Aboriginal stories about objects falling from the sky have led scientists to meteorite finds they would not have known about otherwise.

In New Zealand, geologists are also using Maori oral traditions to study earthquakes and tsunamis. New Zealand has a much more recent human history – compared to Australia – with the first Maori ancestors thought to have arrived around the 13th Century.

The arrival of the first Australians goes back at least 50,000 years. There is still much to learn, as Australia’s ancient landscape has been exposed to meteorite strikes that we don’t know about, some of which have probably occurred since humans arrived.

But given that Australia is home to the oldest continuing cultures on Earth, we are only just scratching the surface of the vast scientific knowledge contained in Indigenous oral traditions.

We anticipate that our work with Aboriginal elders to learn about Indigenous astronomy will lead to new knowledge and cultural insights about natural events and meteorite impacts in Australia.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

↧

Fire in the sky: The southern lights in Indigenous oral traditions

Parts of Australia have been privileged to see dazzling lights in the night sky as the Aurora Australis – known as the southern lights – puts on a show this year.

A recent surge in solar activity caused spectacular auroral displays across the world. While common over the polar regions, aurorae are rare over Australia and are typically restricted to far southern regions, such as Tasmania and Victoria.

But recently, aurorae have been visible over the whole southern half of Australia, seen as far north as Uluru and Brisbane.

Different cultures

It’s a phenomenon that has existed since the Earth’s formation and has been witnessed by cultures around the world. These cultures developed their own explanation for the lights in the sky – many of which are strikingly similar.

From a scientific point of view, aurora form when charged particles of solar wind are channelled to the polar regions by Earth’s magnetic field. These particles ionize oxygen and nitrogen molecules in the upper atmosphere, creating light.

Auroral displays can show various colours, from white, to yellow, red, green, and blue. They can appear as a nebulous glowing arcs or curtains waving across the sky.

Aurorae are also reported to make strange sounds on rare occasions. Witnesses describe it as a crackling sound, like rustling grass or radio static.

In the Arctic, the Inuit say the noise is made by spirits playing a game or trying to communicate with the living.

In 1851, Aboriginal people near Hobart said an aurora made noise like “people snapping their fingers”. The cause of this noise is unknown.

Aurorae are significant in Australian Indigenous astronomical traditions. Aboriginal people associate aurorae with fire, death, blood, and omens, sharing many similarities with Native American communities. They are quite different from Inuit traditions of the Aurora Borealis, which are more festive.

Fire in the sky

Aboriginal people commonly saw aurorae as fires in the cosmos. To the Gunditjmara of western Victoria, they’re Puae buae (“ashes”). To the Gunai of eastern Victoria, they’re bushfires in the spirit world and an omen of a coming catastrophe.

The Dieri and Ngarrindjeri of South Australia see aurora as fires created by sky spirits.

As far north as southwestern Queensland, Aboriginal people saw the phenomenon as “feast fires” of the Oola Pikka —- ghostly beings who spoke to Elders through the aurora.

The Maori of Aotearoa/New Zealand saw aurorae (Tahunui-a-rangi) as the campfires of ancestors reflected in the sky. These ancestors sailed southward in their canoes and settled on a land of ice in the far south.

The southern lights let people know they will one day return. This is similar to an Algonquin story from North America.

A warning to follow sacred law

Mungan Ngour, a powerful sky ancestor in Gunai traditions, set rules for male initiation and put his son, Tundun, in charge of the ceremonies. When people leaked secret information about these ceremonies, Mungan cast down a great fire to destroy the Earth. The people saw this as an aurora.

Near Uluru, a group of hunters broke Pitjantjatjara law by killing and cooking a sacred emu. They saw smoke rise to the south, towards the land of Tjura. This was the aurora, viewed as poisonous flames that signalled coming punishment.

The Dieri also believe an aurora is a warning that someone is being punished for breaking traditional laws, which causes great fear. The breaking of traditional laws would result in an armed party coming to kill the lawbreakers when they least expect it.

In this context, fear of an aurora was utilised to control behaviour and social standards.

Blood in the cosmos

The red hue of some aurorae is commonly associated with blood and death.

To Aboriginal communities across New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia, auroral displays represented blood that was shed by warriors fighting a great battle in the sky, or by spirits of the dead rising to the heavens.

A total lunar eclipse turns the moon red (sometimes called a blood-moon), which was seen by some communities as the spirit of a dead man rising from his grave.

Rare astronomical events were viewed as bad omens by cultures around the world. Now imagine if two of these events overlap!

In 1859, Aboriginal people in South Australia witnessed an auroral display and a total lunar eclipse. This caused great fear an anxiety, signalling the arrival of dangerous spirit beings.

There could be a repeat of this astronomical double-act as a lunar eclipse will be visible across Australia on Saturday April 4, 2015.

Will the aurorae continue? Keep watch.

----

This article was originally published in The Conversation on 2 April 2015, 6.09am AEDT.

↧

↧

Aboriginal languages could reveal scientific clues to Australia’s unique past

↧

Identifying Seasonal Stars in Kaurna Astronomical Traditions

By Duane W. Hamacher

Early ethnographers and missionaries recorded Aboriginal languages and oral traditions across Australia. Their general lack of astronomical training resulted in misidentifications, transcription errors and omissions in these records. In western Victoria and southeast South Australia many astronomical traditions were recorded but, curiously, some of the brightest stars in the sky were omitted. Scholars claimed these stars did not feature in Aboriginal traditions. This continues to be repeated in the literature, but current research shows that these stars may in fact feature in Aboriginal traditions and could be seasonal calendar markers. This paper uses established techniques to identify seasonal stars in the traditions of the Kaurna Aboriginal people of the Adelaide Plains, South Australia.

This paper was published in the

Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, Vol. 18(1), pp. 39–52 (2015)

It is freely available online.

↧

Mauna a Wakea: Hawai'i’s sacred mountain and the contentious Thirty Meter Telescope

By Duane W. Hamacher (University of New South Wales) and Tui R. Britton (Macquarie University)

This article was originally published in The Conversation on September 21, 2015 6.09am AEST.

This article was originally published in The Conversation on September 21, 2015 6.09am AEST.

|

| Hawaii's Thirty Metre Telescope (artists tic design) |

Plans to build a new telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawai'i have led to months of protests and arrests, including several earlier this month. The ongoing protest pitches astronomers against Hawaiians wanting to protect their sacred site.

Conflict between Indigenous and Western interests are part of a long history of colonisation and exploitation. In the Amazon, indigenous communities are fighting governments that exploit the rain forest for natural resources. In the United States and Canada, First Nations people are battling mining and oil interests.

In Western Australia, Aboriginal people are finding their 30,000 year old rock art sites being deregistered as sacred because they must be “devoted to a religious use” rather than be “a place subject to mythological story, song, or belief”. Many of these sites are in areas of industrial expansion.

If the traditional custodians of the land reject proposals for development, they might face aggressive legal action. “No” is rarely a good enough answer for those exploiting the land, and seeking permission from indigenous people often smacks of tokenism rather than a real attempt to address the wrongs of the past.

The mountain of Wakea

Unfortunately, it is not just economic interests that put pressure on indigenous communities. Scientific interests prove another challenge to indigenous land rights. One such case is the development of the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) in Hawai'i.

On Hawai'i’s Big Island stands Mauna Kea, a dormant volcano towering 4,200 meters above sea level. Its high elevation and excellent atmospheric conditions make it an ideal place for astronomers to observe the stars. Mauna Kea is named for the god Wakea, the “sky father” – Mauna a Wakea. It is Hawai'i’s most sacred place.

It is important to note here that only people of Indigenous Polynesian Hawaiian heritage are called “Hawaiian”. Non-Indigenous people born in Hawai'i are called “Kama'aina” meaning “child of the land”, or “people of Hawaii” in general conversation.

Hawaiian reverence for Wakea meant that in ancient traditions only the Ali'i (high chiefs) were allowed to climb to its summit, where their most sacred ancestors are buried. It is here that astronomers plan to build a US$1.5-billion telescope with a primary mirror measuring 30 meters across.

The TMT offers potential scientific discoveries as well as economic benefits for the island. Currently there are 13 telescopes atop Mauna Kea but many Hawaiians are angry about the push to add more telescopes to the mountain, insisting enough is enough.

A resurgence of Hawaiian culture and language has led to the reclamation of sacred sites, including Mauna Kea, as areas of high cultural significance. Hawaiians wanting to preserve their cultural heritage are now clashing with proponents of the TMT. In recent months, protesters have blocked access to the mountain, halting development of the telescope.

An ongoing concern

Should astronomers be allowed to build the TMT on Mauna Kea? This question raises concerns that we, as practising astronomers, see as a reoccurring issue within the scientific community.

It is disheartening and frustrating to witness fellow scientists dismiss the connections indigenous people have to their land. We cannot simply disregard these connections as myths and legends, and comparing TMT protesters to Biblical Creationists is disappointing.

This is not a battle between religion and science. Hawaiians are not anti-science; they are not trying to push their traditional beliefs on others nor are they trying to stifle scientific and economic advancement. They simply oppose construction of yet another telescope on their sacred mountain.

We need to recognise and respect the close connection Hawaiians have to sacred sites like Mauna Kea and not misappropriate Hawaiian astronomical traditions for the benefit of astronomers.

The TMT demonstrates a microcosm of the challenges indigenous people face when their traditions are dismissed by Western interests for intellectual or economic gain.

Moving forward together

We acknowledge that some Hawaiians do in fact support the TMT, while others are calling for the removal of all telescopes. Governor David Ige offered one compromise: the removal of a quarter of the existing telescopes before building of the TMT commences.

We do not have a convenient solution to this issue. So how do we move forward together?

We can look at successful collaborations between scientists and indigenous people on other projects for guidance. The development of the Square Kilometre Array radio telescope in Western Australia was a result of close collaboration and ongoing consultation between astronomers and the traditional owners of the land.

We can take inspiration from the Polynesian Voyaging Society and Hoku'lea – the Hawaiian voyaging canoe. By working closely with artisans, navigators, astronomers, and historians, Hawaiians are reclaiming their ancient knowledge and in turn are sharing this with the world.

These two examples suggest nurturing mutually respectful relationships is the key to overcoming conflict.

This is a highly complex issue. We astronomers need to acknowledge that we do not have an inherent right to develop Mauna Kea. And if a consensus cannot be reached we must be willing to consider a different home for the TMT.

↧

Star Stories of the Dreaming: a Documentary (Trailer)

Euahlayi Lawman and Knowledge Holder, Ghillar Michael Anderson shares some of the ancient wisdoms of his Peoples' connection to the universe. He also speaks with a leading astrophysicist, Professor Ray Norris, as they compare the similarities between astrophysics and Stories older than time itself. Based on research by Robert Fuller.

Location northwest NSW - north of Goodooga.

Filmed by Ellie Gilbert

Researcher: Robert Fuller

Starring: Ghillar Michael Anderson and Ray Norris

↧

↧

How ancient Aboriginal star maps have shaped Australia’s highway network

Originally published in The Conversation (Australia) on April 7, 2016 6.07am AEST

The next time you’re driving down a country road in outback Australia, consider there’s a good chance that very route was originally mapped out by Aboriginal people perhaps thousands of years before Europeans came to Australia.

And like today, they turned to the skies to aid their navigation. Except instead of using a GPS network, they used the stars above to help guide their travels.

Aboriginal people have rich astronomical traditions, but we know relatively little about their navigational abilities.

We do know that there was a very well established and extensive network of trade routes in operation before 1788. These were used by Aboriginal people for trading in goods and stories, and the trade routes covered vast distances across the Australian continent.

Star maps

I was researching the astronomical knowledge of the Euahlayi and Kamilaroi Aboriginal peoples of northwest New South Wales in 2013 when I became aware of “star maps” as a means of teaching navigation outside of one’s own local country.

My teacher of this knowledge was Ghillar Michael Anderson, a Euahlayi Culture Man from Goodooga, near the Queensland border. This is where the western plains and the star-filled night sky meet in a seamless and profound display.

One night, sitting under those stars in Goodooga, Michael pointed out a pattern of stars to the southeast, and said that they were used to teach Euahlayi travellers how to navigate outside their own country during the summer travel season.

As an astronomer, I immediately realised that those stars were not in the direction of travel that Michael was describing. And anyway, they wouldn’t be visible in the summer, let alone during the day when people would have been travelling.

Michael said that they weren’t used as a map as such, but were used as a memory aid. And in the Aboriginal manner of teaching, he asked me to research this and come back to see if “I had gotten it”.

I did some research, and looked at a route from Goodooga to the Bunya Mountains northwest of Brisbane, where an Aboriginal Bunya nut festival was held every three years until disrupted by European invasion.

It turned out the pattern of stars showed the “waypoints” on the route. These waypoints were usually waterholes or turning places on the landscape. These waypoints were used in a very similar way to navigating with a GPS, where waypoints are also used as stopping or turning points.

Stars to songlines

Further discussion revealed the reasons and methods of this technique. In the winter camp, when the summer travel was being planned in August or September, a person who had travelled the intended route was tasked with teaching others, who had not made this journey, how to navigate to the intended destination.

The pattern of stars (the “star map”) was used as a memory aid in teaching the route and the waypoints to the destination. After more research I asked Michael if the method of teaching and memorising was by song, as I was aware that songs are known to be an effective way of memorising a sequence in the oral transmission of knowledge.

Michael said, “you got it!”, and I then understood that the very process of creating, then teaching, such a route resulted in what is known as a songline. A songline is a story that travels over the landscape, which is then imprinted with the song (Aboriginal people will say that the landscape imprints the song).

I then learned that there were many routes/songlines from Goodooga to destinations as far as 700km away, which might end up in a ceremonial place, or possibly a trade “fair”.

One such route to Quilpie, in Queensland, led to a ceremonial place where Arrernte people from north of Alice Springs met the Euahlayi for joint ceremonies.

Their route of travel was more than 1,500km, crossing the Simpson Desert in summer, and I was told that they would have their own star map/songline for learning that route. The implication of this is that the use of star maps for teaching travel may have been common across Australia.

Parallels

Another surprising result of this knowledge came about when I was looking at the star map routes from Goodooga to the Bunya Mountains and Carnarvon Gorge in Queensland. When the star map routes were overlaid over the modern road map, there was a significant overlap with major roads in use today.

After some reflection, the reason for this became clear. The first explorers in this region, such as Thomas Mitchell, who explored here in 1845-1846, used Aboriginal people as guides and interpreters, who were likely given directions by local Aborigines.

These directions would no doubt reflect the easiest routes to traverse, and these were probably routes already established as songlines. Drovers and settlers coming into the region would have used the same routes, and eventually these became tracks and finally highways.

In a sense, the Aboriginal people of Australia had a big part in the layout of the modern Australian road network. And in some cases, such as the Kamilaroi Highway running from the Hunter Valley to Bourke in NSW, this has been recognised in the name.

↧

Article 2

In the previous post, I discussed Arrernte oral traditions relating to the Henbury crater field in the Central Desert. Let us now travel 175 km west of Alice Springs, where we see 5 km-wide ring-shaped mountain range that stands 150 metres above the desert, representing the remnant central uplift of an eroded 22 km-wide complex crater (Figure 1). The scientific explanation is that this structure formed from a comet impact some 142.5±0.8 million years ago. Over that time, the land eroded down almost 2 km in thickness. What we see today as the mountain range is the result of differential erosion, meaning the shocked stone is denser and eroded less than the surrounding landscape.

The Western Arrente call this place Tnorala and consider it sacred. Arrernte Elder Mavis Malbunka (Figure 2), wife of Herman Malbunka, the Traditional Custodian of Tnorala from Ntaria (Hermannsburg), explains the origin of Tnorala in Arrernte traditions and its importance today.

The Western Arrente call this place Tnorala and consider it sacred. Arrernte Elder Mavis Malbunka (Figure 2), wife of Herman Malbunka, the Traditional Custodian of Tnorala from Ntaria (Hermannsburg), explains the origin of Tnorala in Arrernte traditions and its importance today.

Figure 1: Gosse's Bluff, called Tnorala by the Western Arrernte.

In the Dreaming, a group of sky-women danced as stars in the Milky Way. One of the women, who was carrying a baby, grew tired and placed her baby in a wooden basket, called a turna or coolamon. As the women continued dancing, the turna fell and the baby plunged into the earth. The baby struck the earth and was covered by the turna, the force of which drove the rocks upward, forming the circular mountain range we see today. The baby's mother, the evening star, and father, the morning star, continue to search for their baby to this day. She continues:

Figure 2: Mavis Malbunka talking about Tnorala. ABC's Message Stick, 19 July 2009.

Click on the image to see the video clip.

"We tell the children don't look at the evening star or the morning star, they will make you sick because these two stars are still looking for their little baby that they lost during the dance up there in the sky, the way our women are still dancing. That coolamon, the one the baby fell out of, is still there. It shows up every winter." The coolamon is the constellation Corona Australis - the Southern Corwn. It is seen just below the Milky Way and is prominent in the winter night skies (see Figure 4).

Figure 3: A coolamon or turna. Australian Museum.

Figure 4: Corona Australis, the Southern Crown. Frosty Dew Observatory.

Mavis warns visitors to "Be careful at night. These two stars are looking for their child, Tnorala." Still today, that evening star comes at night with big lights. The white man call it Min Min light, but we know it as the bright light of the mother looking for her child”.